About BookScoutPro

BookScoutPro is a webby pricing tool intended for use by book scouts, when they’re out at book sales looking at books and wanting information about whether books they have in hand can be resold quickly for a profit. It is a listing aggregation service that looks up a book against several other sale services and returns pricing and other information from those services.

As such, it is designed for use with cellphone-based browsers with small screens and high-latency (slow turnaround) network connectivity, so it can look up several books in one batch and provide brief results. That it can do these things makes it a useful informational tool for some sections at FOPAL, and perhaps one that lets us separate the task of looking up books from the other work of managing a section.

BookScoutPro’s bases for lookup are the International Article Number (EAN) and International Standard Book Number (ISBN). This means it is not useful for author and title lookups, and is only useful for books published after about 1970 when ISBNs came into widespread use. That’s not as bad as it sounds, many of the books we get were in fact published recently enough to have ISBNs, and many of those were published recently enough to have EANs printed as bar codes which can be scanned with a bar-code wand, which is both easier and more reliable than typing in a 10-digit ISBN.

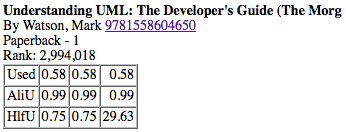

Sample BookScoutPro results

Let’s take a short look at an example of BookScoutPro search results.

Briefly, what this is showing is enough information about the book (title, author, EAN, edition) to identify it, its Amazon sales rank, and a table of three lowest prices from each of three sources. The sales rank can give you some idea of demand for this title at Amazon (a lower number means Amazon sells more of the title), and the pricing information can give you some idea of the price floor for this edition.

So what you want to imagine as a section manager is getting a box of books with a printout on top, that printout having this information for each of the books in the box. Would that be useful to you? Would it help you identify higher-value books? Would it help you identify lower-value, slower-moving books? Would it help you do these things more quickly and more easily?

How To Get There

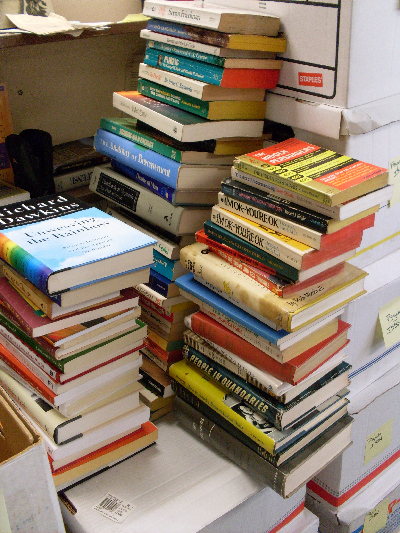

The typical box of books from the sorting room is a somewhat random assortment of what was encountered while sorting, and looks something like the ones in the picture below.

The first thing we need to do is separate the books by lookup workflow. We’ve got three workflows: one for books with EAN-13 bar codes that can be scanned, one for books with ISBNs that can be typed in, and one for books with neither which may need to be looked up by author and title. So we try to sort the books based on which workflow they go with: bar code, ISBN, and neither; once some of that has been done we can get on with looking them up.

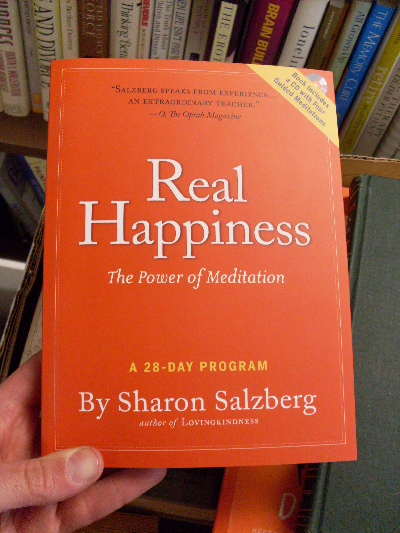

So you pick up a book and look at it. If it has an EAN-13 bar code, this will usually be on the back cover, because book store owners don’t want the point-of-sale staff spending a lot of time and effort hunting for it.

Recognizing Bar Codes

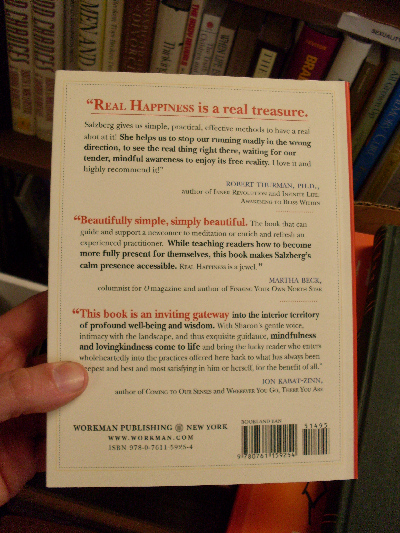

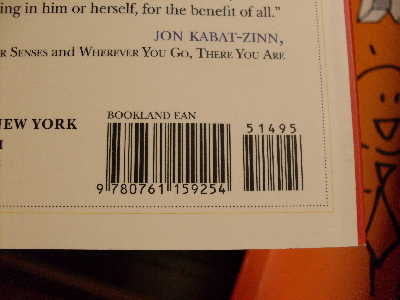

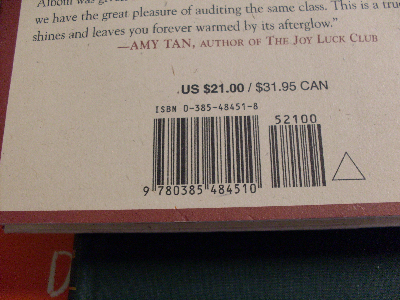

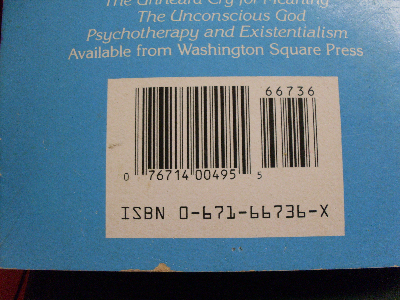

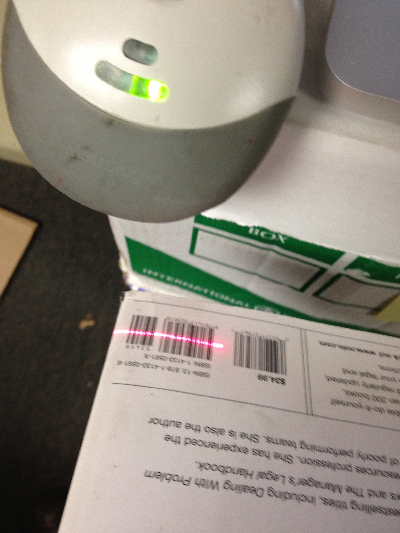

There are a variety of bar codes on the books we receive, and not all of them produce useful results when scanned. Let’s take a closer look at the one from this book.

There are really two bar codes here. The one on the left is an EAN-13 bar code. It represents 13 digits, which are helpfully printed under it so we can see that they start with 978, which is usual for books and other materials produced by book publishers (such as audiobooks). That’s the sort of bar code that we want.

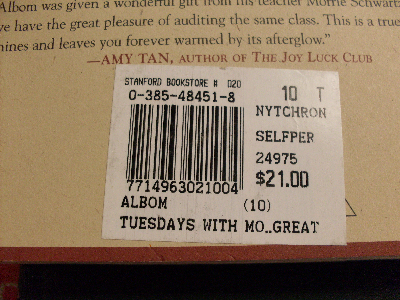

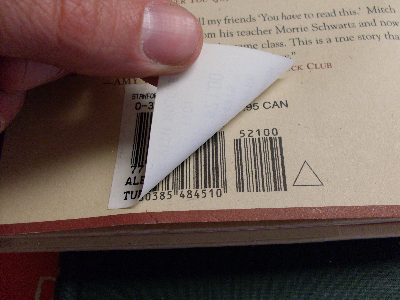

There are other sorts of bar codes that we don’t want. For example, some book sellers like to put their own bar code stickers on books.

Many of these can be removed without too much difficulty. For example, Stanford Bookstore’s stickers usually can be peeled off with fingers, and if it’s a newish book you will likely be rewarded with an EAN-13 bar code that can be scanned.

If removing the sticker looks like too much trouble, it may be easier to look for an ISBN (see below) and sort it out that way.

Some books have other types of bar codes. In the 1980s, before EAN-13 bar codes became popular, it was common for mass-market books to have a 12-digit bar code with a group of five or six digits that identified the producer (publisher) and a group of five digits that directly indicated the producer’s suggested retail price. We can scan those, but they don’t identify the book and so don’t have any use to us. However, these books often have an ISBN printed nearby and can be sorted into the ISBN pile.

Recognizing ISBNs

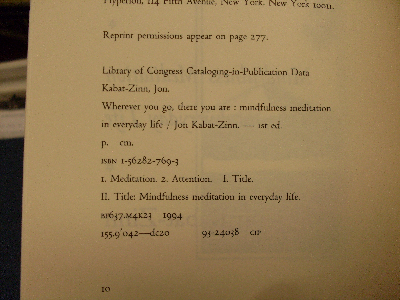

And almost all books that have ISBNs will mention the ISBN in the publication data printed in the book. Of course, you will need to flip through the first few pages of the book to find it, and then it’s often in small type.

As seen above, it is not unusual for books from the 1980s to have an ISBN printed on the back cover or back dust jacket. Some larger publishers took to this practice earlier and so you can find it on Penguin and Prentice-Hall books from the 1970s.

Mass-market paperbacks from the 1970s and 1980s often have something like an ISBN on the cover. Here we have two examples with ISBNs on the spine, with the retail price following.

But you need to look carefully at these, as some publishers omitted portions of the ISBN.

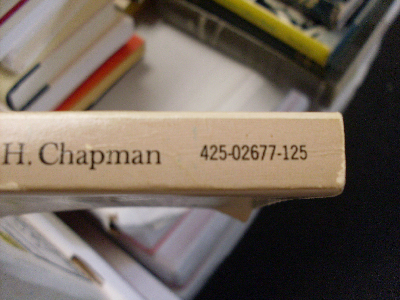

In this case there are only eight digits, followed by a group of three digits which indicate the suggested retail price. If we look inside the book we can find those eight digits with a ninth digit, indicated as an “SBN” which is an earlier “Standard Book Number” that was used in the late 1960s.

The SBN is a precursor to the ISBN, and can usually be “promoted” to an ISBN by putting a 0 digit on the left.

As a rule, books published after about 1970 have an ISBN, and books published after about 1990 have an EAN-13 bar code. There are exceptions, some categories of books (e.g. textbooks) started using the EAN-13 bar code sooner than others, and there are some book-like things published today that are not sold via retail book distribution channels (e.g. books sold primarily by direct sale) and so the publisher didn’t see value in using an ISBN.

So as you’re going about this you’re making three piles of books: books with EAN-13 bar codes, books with ISBNs, and books with neither.

These piles will grow to the point where you want to start boxing the books.

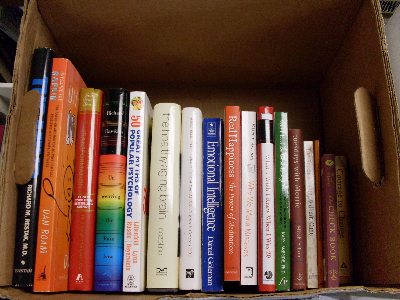

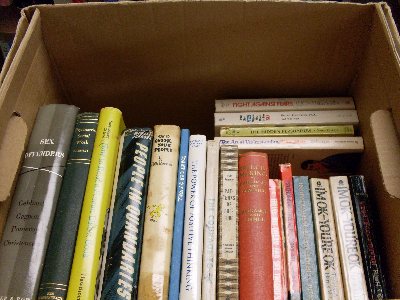

When you put the books in a box, put the first ones in spines up, and down the length of the box. The purpose is to put the books in an order, so that they can be looked up in that order, and left in that order to help the section manager find the book from the order of results on the printout. It is also helpful to sort them roughly by book spine height: this can maximize the gap between the tops of the books and the wall of the box, and you can often fit another three or four books in that gap, and maybe even more if they’re smaller books.

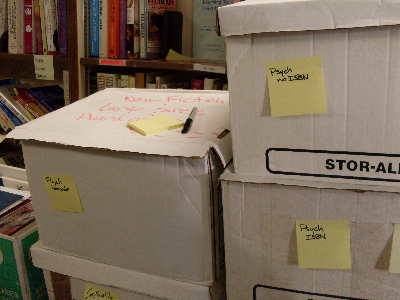

Then you can put stickers on the boxes to indicate what sort of stuff is within, and put lids on so they can be stacked better.

And Now, Looking Things Up

So we’ve done all that and now we can get to looking things up. Start with the boxes of bar coded books, in many sections they will be the largest pile and they are also the ones that can be processed most quickly.

Open up a web browser on a computer with a bar code scanner. Direct the browser to http://web.bsp9.com/ (this may be bookmarked on the computers in the sorting room). It may prompt for a user name and password, which are not given here; you should enter those and then you will get to a lookup form that appears as below.

You may need to click in the text area to get the focus in it. Then you can start waving bar codes in front of the scanner wand to get them read into the text area.

This can be trickier than it at first appears. Many books have the EAN-13 bar code that we want to scan. Some books have other bar codes and if the bar code wand sees one of those first it is likely to scan it instead. So you may need to position the book and/or the scanner wand so that the other bar codes are not in the scanner’s field of vision.

So go through the box, scanning the books in sequence, and replacing them in the box in the same sequence. When you’re done, click on the “Lookup” button and wait a bit to get the results. You can then print those results out from the browser, collect them from the printer in the sorting room, and put the printed results on top of the books in the box for the section manager’s reference.

Sometimes BookScoutPro will not get any results for a book, and will return its report with that book’s ISBN-13/EAN-13 in the text area at the bottom of the report. You should check for the book it didn’t find, and move it to an ISBN box, or to a no-ISBN box if you think looking it up by ISBN will also not work.

Sometimes the failed lookup is for a book with an EAN-13 that starts with “979”. It’s not yet clear whether this is most usually a typo’d EAN-13 or a more subtle problem. Some of the numbers that start with 979 are supposed to be available for use as book EAN-13s but I am not sure any have been assigned.

ISBN books are a lot like bar coded books, except that you do the scanning and enter the ISBN into the text area. You don’t need to enter dashes or dots or spaces between groups of digits. You do need to enter X if that’s what the last digit is. Press return after each ISBN.

Most books with ISBNs have 10-digit ISBNs. More recent books have 13-digit ISBNs, which mostly start with 978 and are in fact the same as the EAN-13 bar codes. You may find yourself entering these for recent hardcover books which have come to us without dust jackets and thus without bar codes.

It is possible to mix both EAN-13 bar code scans and ISBN key-ins on the same lookup. This can be handy if you have a small quantity of books to look up.

One thing you will find is, you make more typos than the bar code scanner does. So when the BookScoutPro returns ISBNs in the text area at the bottom of the report, do look for them, you may well find that the failure to find information is because you typo’d the ISBN by transposing digits or something like that.

Books with neither bar codes nor ISBNs require a different lookup mechanism that takes an author and/or a title. There are several such: Amazon can be used that way, Bookfinder is another such, and there are others. This author’s preference is for AddAll, mostly for reasons of smoother workflow and more printer-friendly reports, but there are sometimes issues with AddAll having cached stale data.

You probably don’t need to print out reports for every no-ISBN book, only the ones that appear to have significant value. For example, in the business books, this author uses these results on-screen to divide (and re-box) the books into two categories: “not so hot” which has (often many) listings under $2.00, and “warmer” if listings start at $2.00 or above. The expectation is that Peter (section manager) will glance at the books in the “not so hot” boxes, pull the one or two that look interesting, and send the rest to the bargain room; and also that he will look through the “warmer” boxes more carefully and still send some of those books to the bargain room.